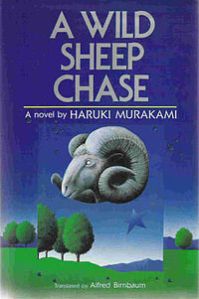

Here are three sentences from Haruki Murakami’s 1982 novel, A Wild Sheep Chase:

Here are three sentences from Haruki Murakami’s 1982 novel, A Wild Sheep Chase:

Nonetheless, the first thing I did upon opening the door to our small, basic hotel room was to grab a slipper to smash a cockroach that was creeping along the window frame. Then I picked up two pubic hairs lying by the foot of the bed and disposed of them in the trash. A new experience for me, seeing a cockroach in Hokkaido.

If you’re like me, you chuckled when you read that. It’s one of many dryly comic passages in the novel. But what makes it funny?

The humour comes from the order in which Murakami arranges his sentences, i.e. the order we receive information. By itself, the fact that the narrator smashed a cockroach and told us that it was a new experience to see a cockroach in Hokkaido doesn’t make me chuckle. Neither does the fact the he picked up some pubic hairs. Consider, for example:

Nonetheless, the first thing I did upon opening the door to our small, basic hotel room was to grab a slipper to smash a cockroach that was creeping along the window frame. A new experience for me, seeing a cockroach in Hokkaido. Then I picked up two pubic hairs lying by the foot of the bed and disposed of them in the trash.

It’s the same paragraph, the same three sentences, but their order has been changed. The second and third sentences have switched places. The biggest change, however, is that it’s not funny anymore.

Murakami makes us laugh by presenting one disgusting act (killing a cockroach) followed by another (picking up someone’s pubic hairs), followed by a single admission: that it’s something new to see a cockroach in Hokkaido. The result is that we understand that it’s not something new for the narrator to be picking up pubic hairs from near a hotel bed. The narrator never says that, but he omits saying it, which we understand to be a tacit admission, which makes us laugh. Eww, you dirty fiend!