If you’ve ever seen Charles Vidor’s masterfully perverse 1946 Hollywood film noir Gilda, you probably remember the opening narration:

To me a dollar was a dollar in any language. It was my first night in the Argentine and I didn’t know much about the local citizens, but I knew about American sailors, and I knew I better get out of there.

The voice belongs to Johnny Farrell, a sly bum of an American gambler who wins some money and gets in trouble for it before being saved by a suave European casino boss, Ballin Mundson, who takes him on as a right-hand man. The titular Gilda is Mundson’s wife, and she and Johnny used to know each other. That brief synopsis doesn’t do the film justice, because Vidor is about style and subtext more than story, but suffice it to say that the effeminate Mr. Mundson has a special cane that hides a sharp tip (“a most faithful and obedient friend”), and things quickly get triangularly Freudian. In no time, Gilda’s shouting, “You’re cock-eyed, Johnny! All cock-eyed!” I hope it sounds bizarre because it is. There’s no way to digest the film seriously, and it’s definitely one of the most brilliant oddities that Hollywood produced in the 1940s. Imagine Casablanca but with less schmaltz and more camp, mixed with sack of crushed-up Viagra pills and run through a meat grinder powered by symbolism.

The voice belongs to Johnny Farrell, a sly bum of an American gambler who wins some money and gets in trouble for it before being saved by a suave European casino boss, Ballin Mundson, who takes him on as a right-hand man. The titular Gilda is Mundson’s wife, and she and Johnny used to know each other. That brief synopsis doesn’t do the film justice, because Vidor is about style and subtext more than story, but suffice it to say that the effeminate Mr. Mundson has a special cane that hides a sharp tip (“a most faithful and obedient friend”), and things quickly get triangularly Freudian. In no time, Gilda’s shouting, “You’re cock-eyed, Johnny! All cock-eyed!” I hope it sounds bizarre because it is. There’s no way to digest the film seriously, and it’s definitely one of the most brilliant oddities that Hollywood produced in the 1940s. Imagine Casablanca but with less schmaltz and more camp, mixed with sack of crushed-up Viagra pills and run through a meat grinder powered by symbolism.

But what is it about Argentina—where lately I’ve found myself trapped in books, film and music—that brings out such strangeness in people?

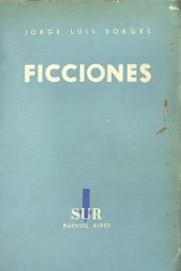

Jorge Luis Borges

Borges liked loops and cycles, which is fitting because every time I read a Borges story I ask myself, “The hell?” and immediately start reading the story again from the beginning. My latest adventure is Borges’ favourite of his own stories, “The South”. Although less immediately the-hell?-ish than many other Borges tales, you don’t have to wade too deeply between the lines to realize that what’s on the surface isn’t right. A man with his nose in a book rams his head on a freshly painted door jamb. His head hurts hellishly. He goes to a sanitarium, where they poke him with needles and now he really thinks he’s in hell. He’s let out. He takes a train south. On the train, he tries reading the same book that led to his head injury but doesn’t get very far because reality’s too absorbing. The trouble is the train seems to be travelling not only south, but also into the past. What’s real? You can read the ending for yourself. I don’t know if “The South” is a good entry point to Borge’s fictions because I’m not yet sure what I think about it, but it’s certainly not as immediately impressive as a story like “The Tower of Babel”. That might be a compliment.

Borges liked loops and cycles, which is fitting because every time I read a Borges story I ask myself, “The hell?” and immediately start reading the story again from the beginning. My latest adventure is Borges’ favourite of his own stories, “The South”. Although less immediately the-hell?-ish than many other Borges tales, you don’t have to wade too deeply between the lines to realize that what’s on the surface isn’t right. A man with his nose in a book rams his head on a freshly painted door jamb. His head hurts hellishly. He goes to a sanitarium, where they poke him with needles and now he really thinks he’s in hell. He’s let out. He takes a train south. On the train, he tries reading the same book that led to his head injury but doesn’t get very far because reality’s too absorbing. The trouble is the train seems to be travelling not only south, but also into the past. What’s real? You can read the ending for yourself. I don’t know if “The South” is a good entry point to Borge’s fictions because I’m not yet sure what I think about it, but it’s certainly not as immediately impressive as a story like “The Tower of Babel”. That might be a compliment.

Leopoldo Torre Nilsson

Contemporary South American cinema has had its share of commercial and artistic successes, but older South American films rarely get the attention of their Euroasian counterparts. Brazil’s Cinema Novo is the exception. Granted, not many South American films are available with English subtitles, but there are definite gems worth searching for. One of the continent’s interesting figures is the Argentine writer and director Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, who made roughly a film per year from 1950 to 1976. He died in 1978. If you understand Spanish, YouTube has the following:

- Piedra libre (1976)

- La guerra del cerdo (1975)

- El pibe cabeza (1975)

- Boquitas pintadas (1974)

- Los siete locos (1973)

- La maffia (1972)

- Martín Fierro (1968)

- La chica del lunes (1967)

- Los traidores de San Ángel (1967)

- El ojo de la cerradura (1966)

- La terraza (1963)

- Setenta veces siete (1962)

- La mano en la trampa (1961)

- Piel de verano (1961)

- Fin di fiesta (1960)

- La caída (1959)

- El secuestrador (1958)

- La casa del ángel (1957)

- Graciela (1956)

- El hijo del crack (1953)

- El crimen de Oribe (1950)

Los Random

In a phrase Borges might enjoy: like but opposite to the character in “The South”, I am travelling in my imagined Argentine both north and into the future. Borges was born in 1899, Nilsson in 1924. Both were born in the capital, Buenos Aires. My current Argentine musical fascination hails from the more northern San Miguel de Tucumán and released their latest album, Pidanoma, earlier this year.

Los Random are a trio and they describe their music as taking “the listener through marshes, with a constant feeling of stress”. The image works. When I listen to Pidanoma, I fly above exotic swampland, sometimes high enough for the terrain to look like circuit boards, and sometimes so low that I have to swat away buzzing insects and swerve between the black trunks of dead trees. It’s narrative music, not in the sense that it tells a story but that my mind weaves stories when I inject it into my brain through my headphones. It sounds like spicy soup tastes. It’s heavy and I’ve seen it tagged sludge, but it’s not sludge. It’s too precise and too jazzy. Maybe “experimental metal” fits better, not just musically but also by associating the sound with alchemy. Sometimes when I listen to it I feel upside down and inverted, as if I’m no longer the eyes floating across the swamp but the swamp over which eyes are floating. Can music turn you into a landscape? The Mexican composer and musician Adrián Terrazas-González, previously a member of The Mars Volta, plays saxophone on “Mee Chango”. And now my coffee’s spilled all over the floor, which is now the ceiling, and I’m about to walk down the hall, stepping over the light that used to shine from above and is now a half-dome over which I must be careful not to trip as it illuminates the world like an incandescent bubble of muculent bog water. When the bubble pops, we all pop with it. The directions revert. I walk on a floor that was floor, until I press the play button and start the whole album from the beginning, like a short story by Jorge Luis Borges.